May 13, 2019

Fight against trans-fatty acids

Hyderabad: There is a sense of urgency and a concerted effort has been launched by national and international government agencies and organisations in the field of public health to limit consumption of Trans-Fatty Acids (TFA) in our daily diet in the next few years.

The seriousness with which World Health Organisation (WHO) and Indian food regulatory agencies, including Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) are targeting food with trans-fat is understandable, given the direct link of TFA to cardiovascular ailments and deaths.

In India, trans-fatty acids are commonly known as Vanaspati, which is directly linked to causing heart diseases. In fact, according to WHO, every year TFA on an average causes an estimated 5 lakh deaths globally. In the first week of May, the WHO achieved a major feat when it convinced International Food and Beverage Alliance (IFBA) to work for elimination of industrially produced TFA from food supply chain by 2023. Last year the FSSAI has launched a campaign to eliminate use of Vanaspati in India by 2022 through active engagement with industries.

So why Vanaspati is bad for us?

Vanaspati or Trans-fatty acids (TFA) are not natural and are prepared through an industrial process known as hydrogenation, which in simple terms is hardening or solidifying vegetable oils. TFA also occurs naturally but at very lower quantities in meat and dairy products from cattle, sheep, goats, and camels.

In India, Vanaspati is still used as a substitute for ghee in cooking and the preparation of bakery products, sweets and snack foods. These oils are most frequently found in baked and fried foods, prepared or pre-packaged snacks and food, and cooking oils and spreads.

Initially developed as a replacement for animal fats such as butter, TFA are now increasingly utilised by industries because they provide longer shelf life to oils and food products. Moreover, TFA are far cheaper than animal fats and also change the texture and taste of food.

Industrially produced TFA were first introduced into the food supply in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the invention of partially hydrogenated oils. Partially hydrogenated oils became more popular in the 1950s-1970s. However, by the late 20th century, an extensive body of evidence had accumulated from various studies on the negative metabolic effects of TFA as well as on the relationship between TFA intake and coronary heart disease.

TFA and its impact on health:

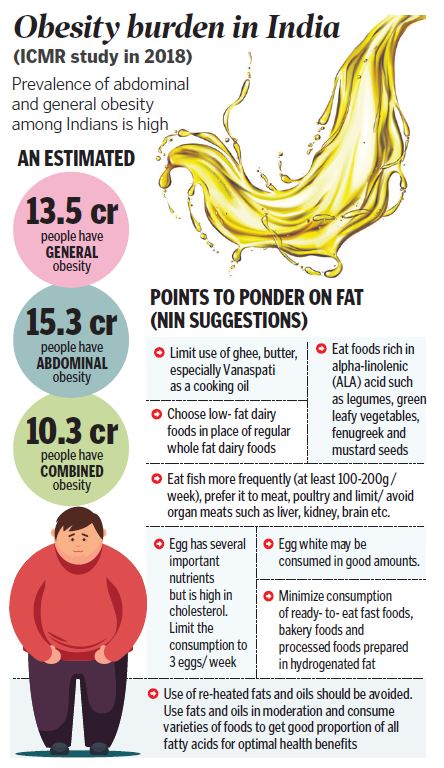

In the last few years, a series of international and national research papers have directly linked TFA to coronary heart diseases (CHD). According to Hyderabad-based National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), the daily intake of TFA should not exceed 1 per cent of energy intake.

Doctors and researchers have also found that TFA causes a rise in LDL Cholesterol levels (Bad cholesterol) and lowers good Cholesterol (HDL). It also increases risk of developing heart disease and stroke and is associated with a higher risk of causing type 2 Diabetes.

According to the WHO, ‘replacement of TFA with unsaturated fatty acids decreases the risk of CHD, in part, by ameliorating the negative effects of TFA on blood lipids. In addition, there are indications that TFA may increase inflammation and endothelial dysfunction’.

How much TFA is good?

WHO recommends that total TFA intake be limited to less than 1 per cent of total energy intake, which translates to less than 2.2 grams per day in a typical 2,000 calorie diet and elimination of industrially-produced TFA from the food supply is critical to achieving this aim.

By decreasing the risk of CHD events and mortality, it will help reduce premature death from NCDs, one of the health targets of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Elimination of industrially-produced TFA will also contribute to the creation of an enabling food environment which promotes healthy diets and help achieve the global nutrition and diet-related NCD disease targets.

FDA warns mango growers: Ripen them naturally or face action

Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) has permitted ethephon powder to be used to ripen mangoes. Last year, after the mango season FSSAI published it directive on August 16.

Food and Drug Authority (FDA) has warned that mangoes should be ripened naturally or it would take action. Directive after research Merchants throughout the Country still use calcium carbide for ripening mangoes.

This banned chemical causes cancer and has been proved through research. Hence the government takes strict action against merchants who use this banned substance.

Noted the merchants started using ethephon powder but FDA official stock action against its use too. Many samples were taken from Kalamana market and sent for analysis. FSSAI, after the season, directed that ethephon powder could be used and so all merchants are using this powder.

FSSAI claims that mangoes, ripened through this chemical, were nutritious. Mangoes ripen due to ethylene gas Cheap ethephon powder is imported in large quantities from China and South Korea.

A pouch of this powder kept in a box emanates ethylene gas and ripens the fruit faster which can be brought to the market. Earlier, the grass kept in the mango box also used to give out ethylene gas and ripen the fruit.

However this process is time consuming and merchants want to make profits faster. Powder should not touch fruits FSSAI directive stipulates that, ethephon powder should not directly touch the fruit. If it touches, it can cause serious diseases. The pouch has to be kept in the box.

Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 has prohibited the use of calcium carbide and action is taken against the individual using it under Sec 59 of the Act.4 Kalamana merchants have gas chamber.

Four merchants in Kalmana have gas chambers for ripening mangoes where ethephon powder is used. Construction of the chamber requires large amount of land and money. Hence small merchants do not construct such gas chambers and ripe mangoes inboxes with ethephon powder.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)